We catch up with Dr Heather Felgate, a post-doctoral research associate at Quadram Institute who is part of work package 2 for Elemental.

Dr Felgate is studying how the biofilms of Shewanella oneidensis and Geobacter sulfurreducens bacteria could help clean up metals from wastewater.

The term bioremediation describes when we use microorganisms, such as bacteria and yeast, to clean up contamination.

Metal contamination in wastewater is a huge environmental issue as many metals in high concentrations can be toxic if present in drinking water. They can cause organ damage and cancer, as well as damage to aquatic ecosystems.

My current aim is to engineer bacteria that can remove metals from wastewater and other types of waste from industry.

I’m working as part of the Engineering Biology Mission Hub called ELEMENTAL which applies engineering biology to address pressing environmental challenges around metal waste, scarcity, and sustainable recovery. The UKRI-funded hub, led by Professor Martin Warren, brings together the Universities of Durham, East Anglia, Manchester, Surrey, York, University College London with the Natural History Museum and the Quadram Institute.

Using Shewanella oneidensis and Geobacter sulfurreducens bacteria to soak up metals

I am currently working with two different bacteria. Shewanella oneidensis and Geobacter sulfurreducens.

Both bacteria are found naturally in the environment and are interesting as they carry out their respiration on the outside of their cell in their outer membrane.

This outer membrane respiration makes them interesting because to carry out respiration they often use metals found in the environment to gain electrons, which are small parts of an atom that are required in respiration.

They stick these metals to their membrane, so they kind of act like magnets. Shewanella oneidensis and Geobacter sulfurreducens’s ability to attach metals from the environment makes them of real interest for the bioremediation of metals and other environmental research.

This is S. oneidensis growing as a biofilm in small tube 70 µm wide (0.07mm). To ensure the biofilm is stable we have to constantly flow through media (bacterial feed) to ensure there is enough Oxygen. A drop in oxygen can cause the biofilm to fall apart. Thanks to Dr Leanne Sims for the image.

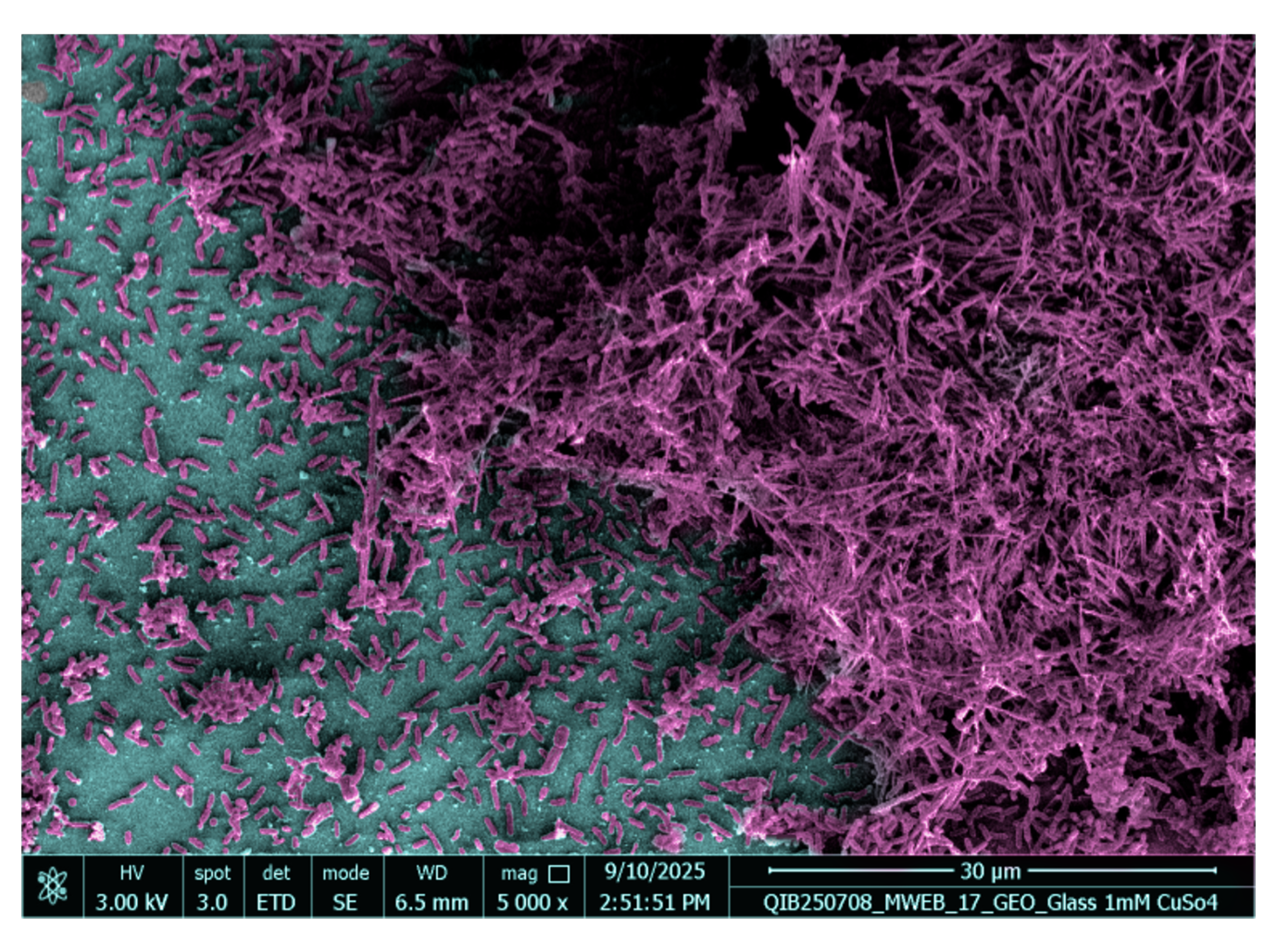

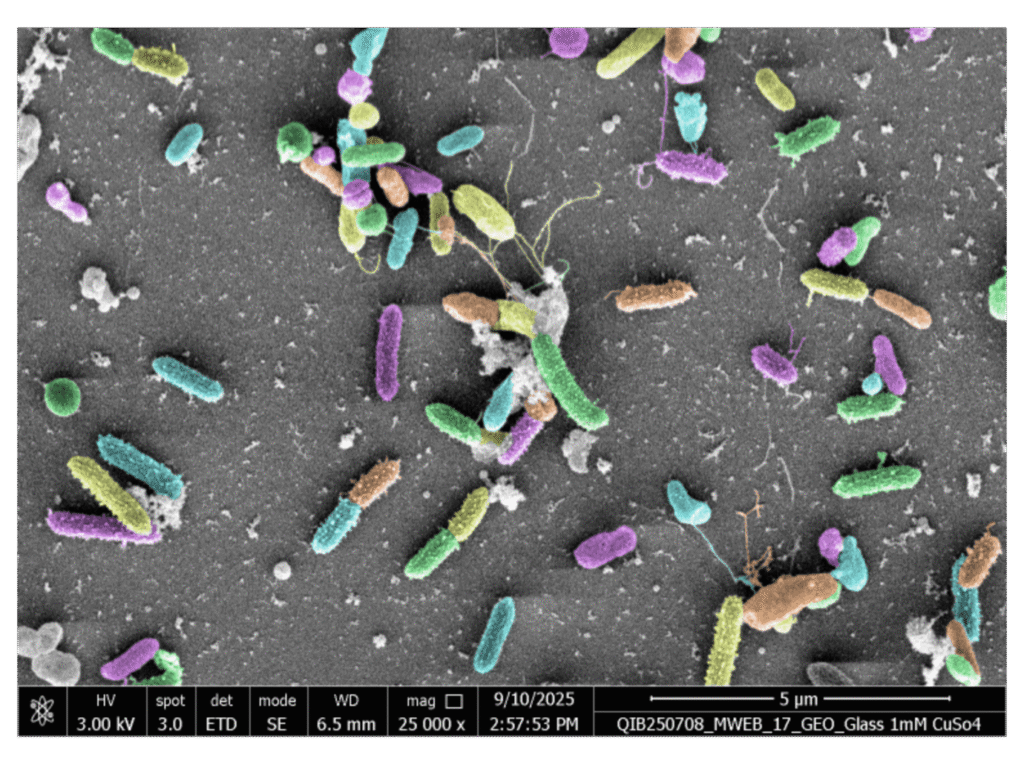

A Geobacter sulfurreducens TraDIS-Xpress library (artists interpretation). Each cell in a TraDIS library is different, we randomly insert a large fragment of DNA called a transposon into each cells genome creating a library of different mutants. We can then observe what genes are essential in a stress, such as high metal concentrations. This SEM image was take by Kathyrn Gotts (QIB Microscopy Department). Image is false coloured, Magnification x25000

Better biofilms to boost bioremediation

Most bacteria that occur naturally in the environment exist as part of a biofilm. Biofilms are groups of microorganisms that have come together as a community on a surface.

In order to understand the biology of these bacteria, in the lab we grow them on glass discs in plastic plates or in small tubes with a flow of feed. Having them in these controlled environments helps us to work out their biochemistry and their biofilm formation.

G. sulfurreducens is excellent at forming biofilms in anaerobic environments, where there is no oxygen, in the presence of high concentrations of toxic or rare Earth metals.

S. oneidensis, however, is terrible at forming biofilms, but its ability to use metals is favourable. Therefore, we are working on creating mutants and evolving S. oneidensis to make better biofilms that we could potentially use to remove metals from the environment.

We are also looking at creating biofilms with both the bacteria together, combining the efforts of both these bacteria.

Using functional genomics to find the better biofilm producers

We are engineering bacteria with better biofilms to clean up contaminated water by using a functional genomics technique called TraDIS-Xpress. TraDIS-Xpress is a method that has been developed to screen thousands of mutants simultaneously.

Using this method, we can find genes that are essential in certain metal stresses and can work out what makes the bacteria use and stick to different metals. This knowledge can then be translated to use the bacteria’s abilities to help clean up environments.

It’s great to be doing this research as part of the Engineering Biology Mission Hub ELEMENTAL which applies engineering biology to address pressing environmental challenges around metal waste, scarcity, and sustainable recovery.

One of the many goals of the ELEMENTAL research hub is to create a more circular economy. By this we mean recycling metals that are found in the waste water system as well as in industrial waste or contaminated waste. Stripping the metals from waste and recycling them back into the creation of new electronics. This therefore will reduce the need for mining the Earth for these rare metals.

Learn more about ELEMENTAL, including the opportunities the hub offers its members and how to join, here.

Banner image: Geobacter sulfurreducens biofilm grown in the presence of 1mM CuSO4 on a glass disc. This SEM image was taken by Kathyrn Gotts (QI Advanced Microscopy). Image is false coloured, Magnification x5000.